21 Jan Calling All Reliability Engineers : What you don’t know about commercial painting, coatings and corrosion is costing your facility a fortune

My itty-bitty consulting firm, Chicago Corrosion Group, has one core principal upon which it is built – to tell the truth at all costs. This is a double-edged sword because, on one hand I embrace the work and love simply telling the truth every single day. On the other hand, it’s bad for business.

Just this past summer, one of the largest health care insurance companies in the world called me out to look at a large, concrete basin that had been coated several years prior. The coating, a polyurea that had been applied between 40 and 80 mils, was slightly mottled and had a handful of blisters and other minor modes of distress. But I would guess that less than 2% of the entire coated surface was distressed, and in every case, the distress was isolated and discrete.

Author was hired to do a failure analysis of a large above ground storage tank. In this case, the depth of the profile was acceptable, but it was not angular in nature, and, therefore, lead to premature failure of the coating system.

The owner, and their team of reliability engineers, had called out to a variety of different companies to get advice, and quotes. All of them recommended complete removal and replacement of the coating system.

One quote was for roughly $180,000 – just to remove the existing material back to bare concrete.

Another quote was nearly double that to remove the material and reapply the same material.

There were four quotes in total, all of which indicated that the existing coating required complete removal.

At the end of our meeting, I was brought into a conference room with 6 different engineers (3 were reliability engineers) and they asked my opinion.

I swallowed hard, as I knew I was about to talk myself out of a yet another job, but said, “I’d repair the damaged areas and leave the rest alone. There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with this coating system”.

They were stunned. Why was my opinion diametrically opposed to everyone else they’d asked?

I explained that our firm was vendor neutral. We charge set fees for our technical advice and always do what’s in the best interest of the client. All of the other vendors only made money if the client spent money. The more money the client spent, the more money the various coating companies and contractors made.

I went on for about 20 minutes about the technical justifications for my thoughts which, of course, were accurate, intuitive and correct.

The material was well-adhered to the substrate. It was cohesively intact. It was monolithic in nature (no apparent holidays or voids). It just didn’t look good and had some blisters.

This story ended well for everyone, other than the aforementioned bidders.

The client hired us to:

- Perform a condition survey to ensure that the coating was sound. This included conducting pull tests and other destructive testing.

- Write a mitigation specification that included overcoating the existing system.

- Develop a proof-of-concept plan, and project-manage a mockup where we applied various coatings, with varying degrees of surface preparation, and then perform destructive testing on the test areas.

- Write application specifications and provide QA during application.

The benefits to the client were immense:

- They saved a small fortune by not having to remove the existing coating (roughly $220,000.00).

- They were able to leave the existing coating in place, where it will continue to provide additional, long-term protection of the concrete substrate.

- The material we selected for overcoating is a thinner elastomer which is aesthetically pleasing and durable, and has an infinite recoat window, making repairs simple (it can also be applied underwater).

- We were able to secure a 5-year warranty, which is practically unheard of in the industry when overcoating an existing material, on both labor and material.

Reliability Engineers are at Particular Risk

Almost without exception, the reliability engineers I’ve worked with are a smart, savvy, detailed bunch of folks. They are appropriately skeptical and ask excellent questions.

Our difficulty has always been in getting their attention – and getting in front of them?

Why?

Because when it comes to commercial painting, coatings and corrosion, they’ve been sold a bill of goods. Reliability engineers typically rely upon coating companies or contractors for advice and direction on how to manage corrosion and paint issues – be it piping, corrosion under insulation (CUI), tank linings, floor coatings, secondary containment, etc.

The problem lies in the fact that commercial painting, coatings and corrosion mitigation are much different than other technical challenges engineers face.

Why?

Because other challenges can be accurately measured – and it’s much easier to compare apples to apples. If you need a pump, you can write a spec and get similar quotes, based on exact specifications. If you’re purchasing pipe, tanks, electronics or virtually anything else, there are very specific, quantifiable parameters to follow. You can match apples for apples.

Not so with paints and coatings, though the paint and coating companies would have you think so.

Let’s look just for a moment at one, very simple aspect of a typical commercial painting practice on steel – or any metallic, for that matter.

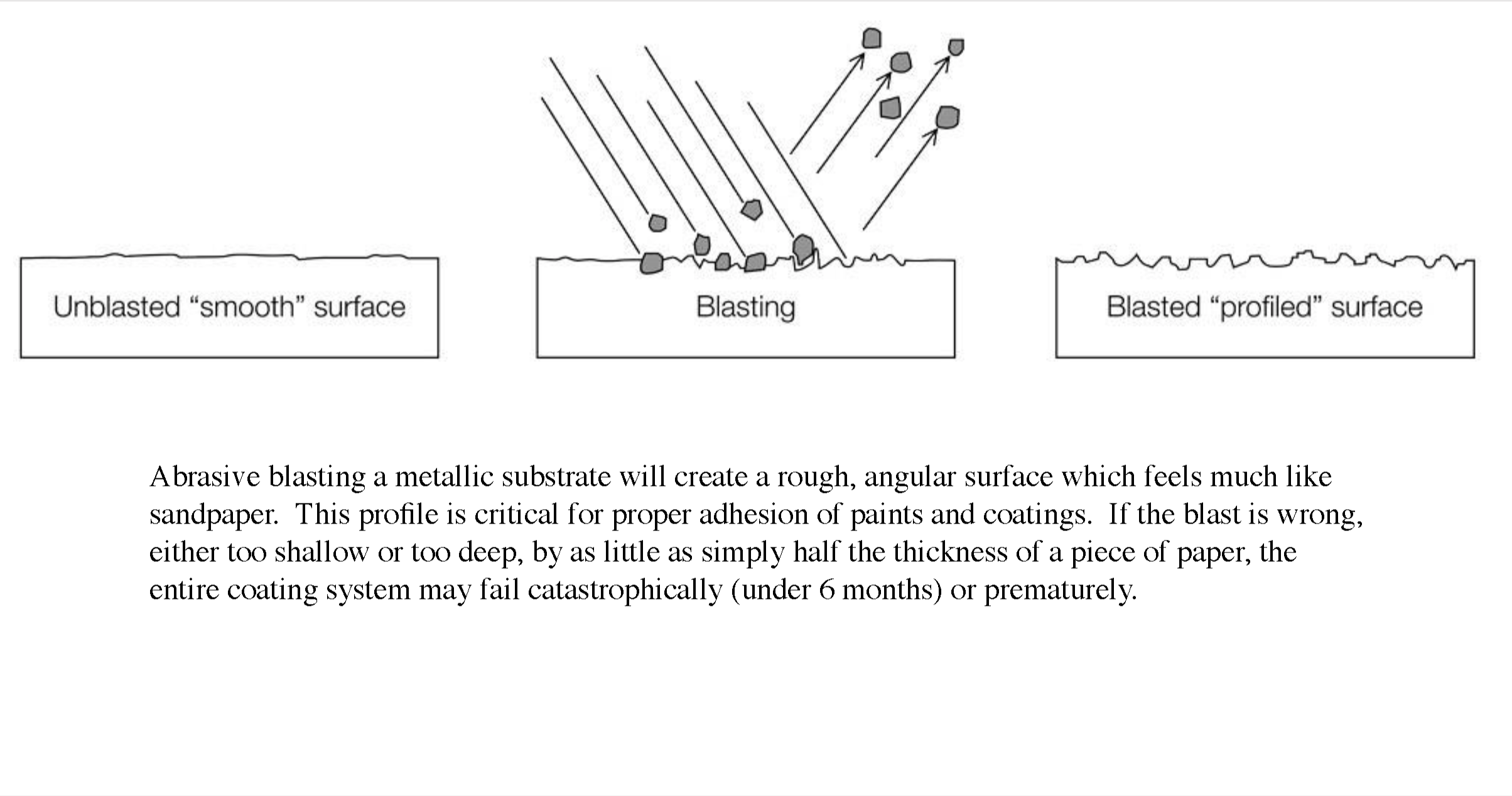

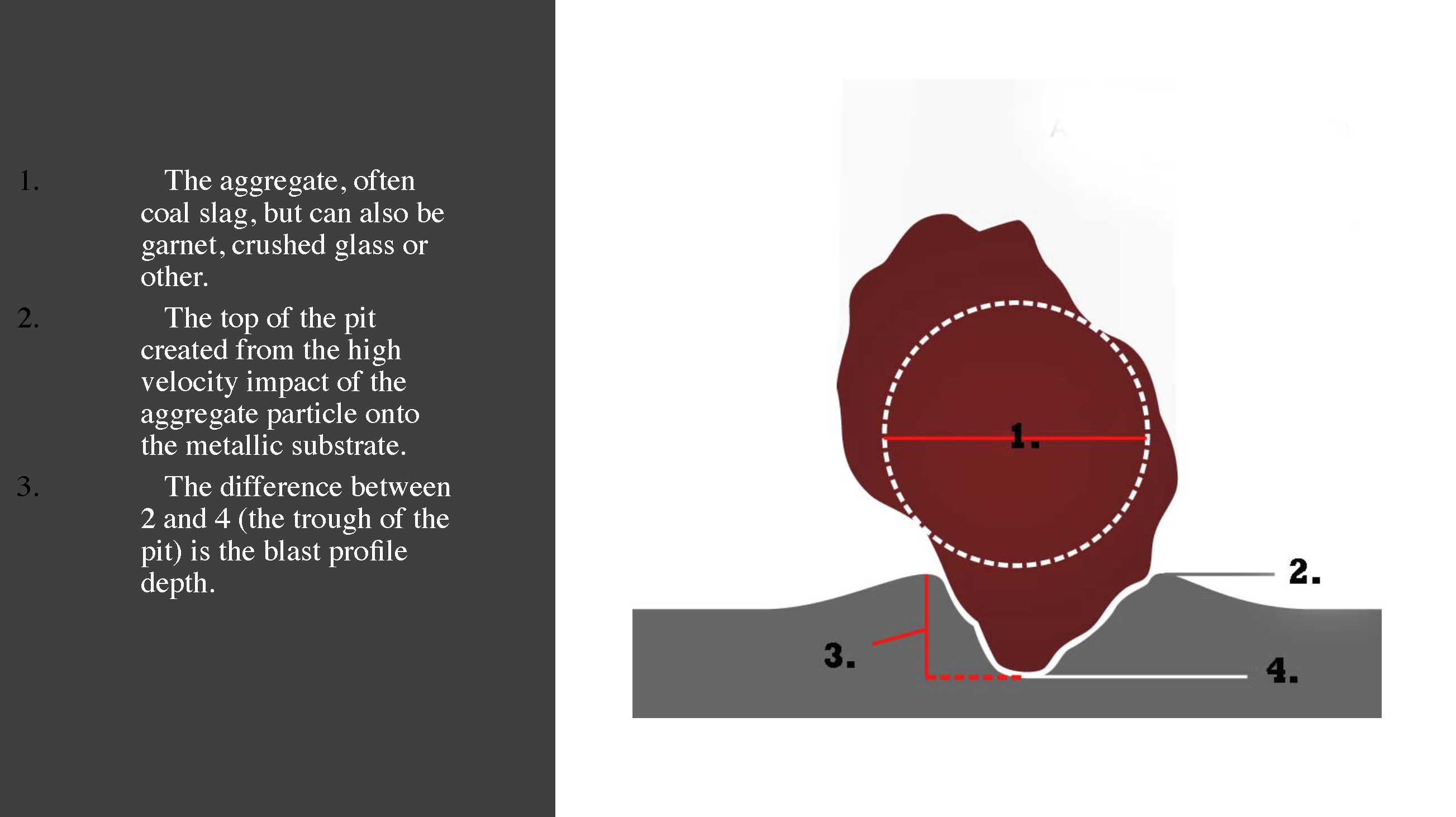

Abrasive blasting.

Manhole in background, tank floor is exhibiting isolated disbondment of the coating system due to an improperly abrasive blasted surface

An abrasive blast profile is measured in mils – with 1 mil being 1/1,000th of an inch. There’s also a visual component of a blast profile which measures how clean or “white” the substrate is. There is near-white (SSPC-SP 10 NACE 2), and white (SSPC-SP 5, NACE 1).

The difference in the long-term performance of a paint or coating system between a blast profile of, say, 1–2 mils at a near-white or commercial blast and a blast profile of 4-6 mils and a white metal blast, might be the difference between a coating system lasting 3-5 years and 20-30 years.

Just think about this for a moment. Where a typical sheet of paper is 4 mils thick, the difference of a half of sheet of paper, can dictate whether you paint something again in 6 years or in 30 years.

If you don’t understand the last two paragraphs – shame on me. Please read them again, and if you still don’t understand them, shoot me an email or call me. This is really, really important.

If, as a reliability engineer, you don’t understand the difference between a near white, and white blast, or differences in profile depth – you are at a substantial disadvantage when working on paint, coating and corrosion issues.

It gets exponentially more complicated when you begin to talk about paint and coatings choices, as there are literally thousands of varieties. Even when talking about one class of coatings, such as epoxies, it needs to be understood that there are so many different types of epoxies that talking about them is like talking about modes of transportation; do you need a sail boat, an airplane, or a hot air balloon? Coating companies will, nearly inevitably, sell you what’s in their best interest, and not yours.

Reliability engineers need to understand that when dealing with corrosion, painting, coating and other similar technologies, they must be exceptionally savvy and critical.

Why?

Because paint companies and contractors are not in the business of providing optimal or exceptionally long-term solutions. Why would they be? Why in the world would a paint company or contractor recommend a coating system that will last for 30 years? What’s in it for them? It’s much more beneficial to them to recommend a coating system that will last for 3 to 5 years – or 8 to 12 years, so that they can sell you another coating system within a reasonably predictable timeframe.

Reliability engineers are often busy and overwhelmed. They need to be conversant on a wide swath of topics. But paint, coatings and corrosion are different – and require additional vetting which may be different than other challenges

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.